Short story

The painter without signature

This year won’t be about grades. I’d rather get a C from him than an A for splashing out paint, Cesar thought on the way to the painting class audition. When he got to the main gate, he stopped for a second to look at a column with a bronze plaque. That reminded him of two students who had dropped out of this class during the first month last semester. He knew they were remarkably talented, so he was wondering if they had been poisoned by the prestige of grades.

In the line for the audition, he noticed the student in front hadn’t brought student‑grade oils, but Olholla ones.

“Melissa, make sure you don’t oversaturate the skin,” he said.

“Envy,” she responded without turning her head.

He had always wanted to paint with them, so he wondered: Is this envy?

“Melissa, he’s right. I wouldn’t use them,” said another student.

That’s en…! Cesar thought in relief. Someday I’ll understand why some people don’t want others to have good things.

In the classroom, only the sound of moving chairs could be heard. The easels were arranged in an arc, and in the middle stood a girl in a Chinese dress, ready to pose.

Is this the big secret test? A live portrait of a girl? No poses, no wrinkles? he thought, not realizing that his friends hadn’t said what happened in the audition.

He prepared his brushes and took a quick look at the girl, which reminded him of rule number one: don’t make a kid stay still for long. The light… is it too bright for her? he thought while carefully looking at her eyes. After seeing no hint of discomfort, he wondered: Who is this girl?

When he was about to pick up his paint tray, the teacher stood up from his desk and gave each student a piece of paper and a pencil, but no eraser. Cesar looked at Maria and their faces said: One mistake and we’re out.

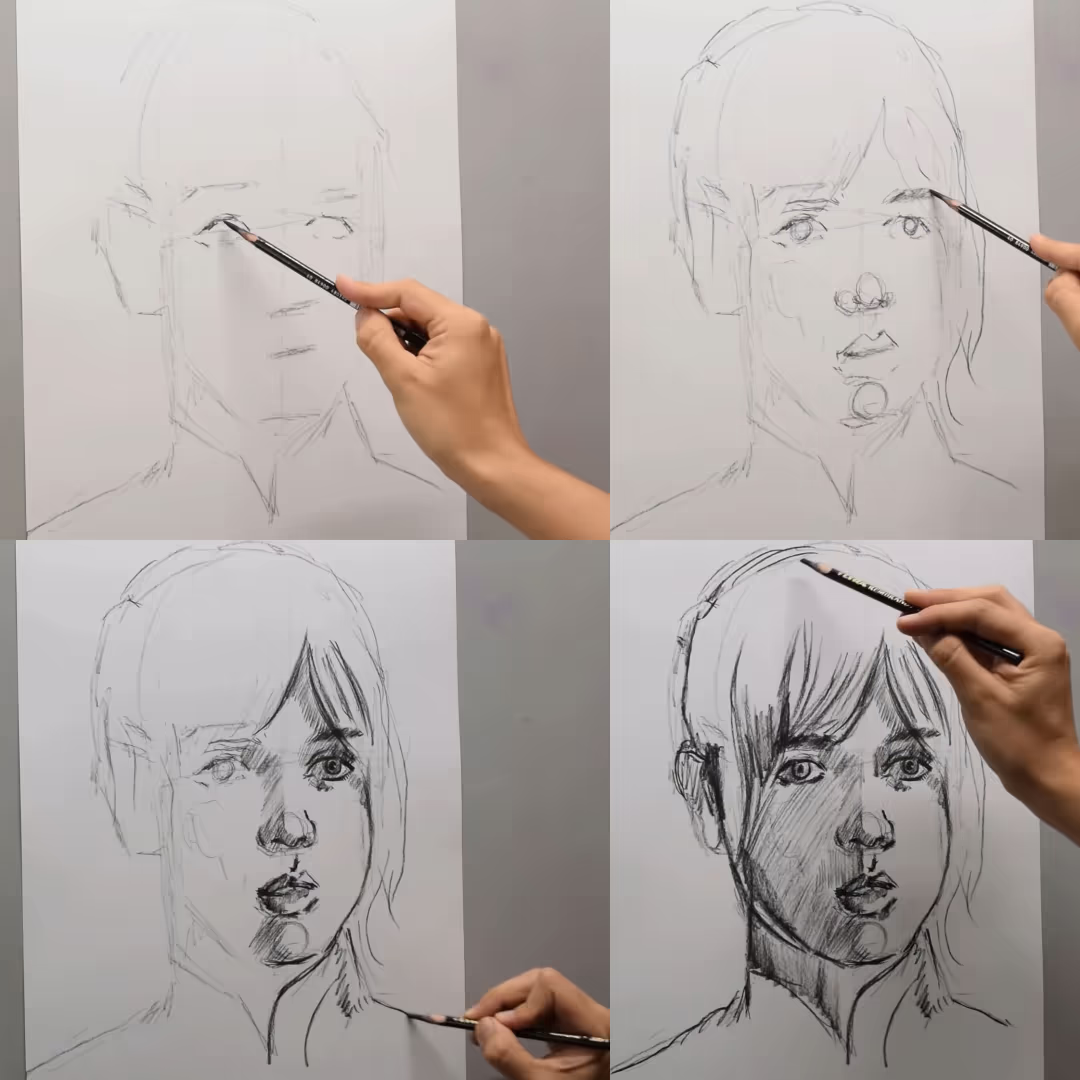

The teacher walked up to the girl. Then, palm up, slowly raised his arm and pointed to her face. Cesar took a deep breath and thought: Showtime! He was no longer worried about making a mistake. He sketched her like a master, not with his wrist but with his arm. In no time, he had blocked out a well‑proportioned face and finished the drawing in two minutes.

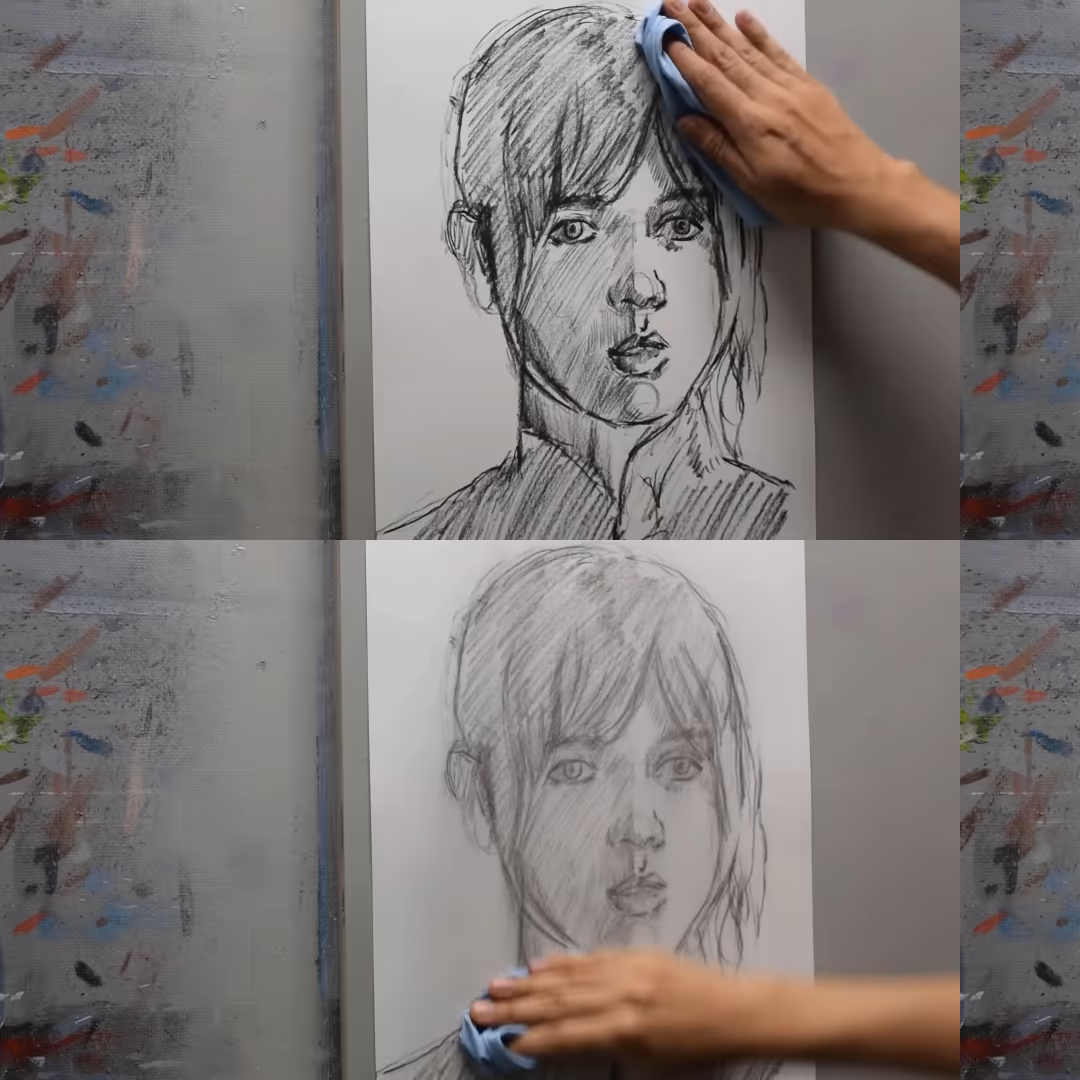

The teacher silently walked behind the easels, and when he saw that Cesar had finished drawing. “Do it again. Here’s a rag.”

Cesar made a concerted effort not to say anything or make any gestures. He remembered: I’m here to show him what I’ve got.

While wiping off the drawing, Cesar noticed her eyes and lower lip were off. That’s the problem, he thought – not in frustration but in satisfaction. Not the satisfaction of having found a way to improve, but of already having it fixed. To him, spotting a bad form and correcting it were parts of an inseparable phenomenon, like oxygen and fuel for a fire.

Ready to fix it, he grabbed an eighty‑grit sandpaper from his bag and rolled the pencil on it until it had a long tip. He drew a line along his thumb to feel its sharpness, and before finishing the line, he pressed his thumb on the sandpaper. My fingerprint, he thought.

When he finished drawing her, the teacher looked at him and made a small circle in the air with his index finger. Cesar quickly wiped off the drawing again.

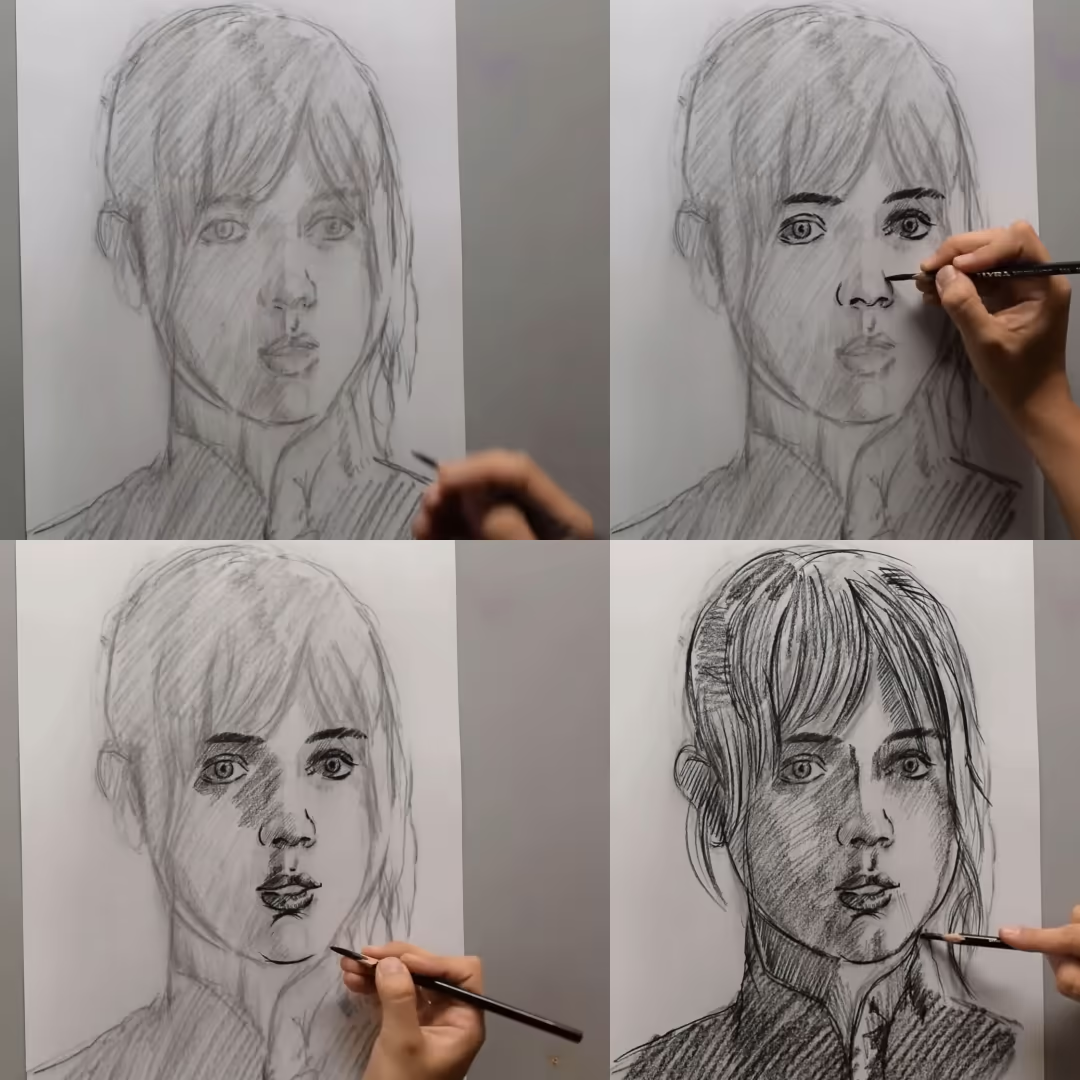

Cesar noticed that the more details he added the muddier the drawing became. He stopped drawing. I’m out. The simplest portrait and I botched it.

When the teacher took a look at the drawing, Cesar tried to catch his eyes for any hint of expression, but it was too late; he had already turned back to his desk.

Then the teacher returned to Cesar and gave him a kneaded eraser and an eraser pencil. “Pull out the highlights.”

Cesar smiled for the first time in that room. He brought out the catchlights in her eyes and ended with the rim light on her ear. He stepped back to see the full portrait and was amazed to see himself rendering such a realistic result.

I didn’t draw beauty, I uncovered it. He imagined the great Michelangelo Buonarroti chiseling out the finest marble and made a pact with him: Yes, knowing what to remove is important.

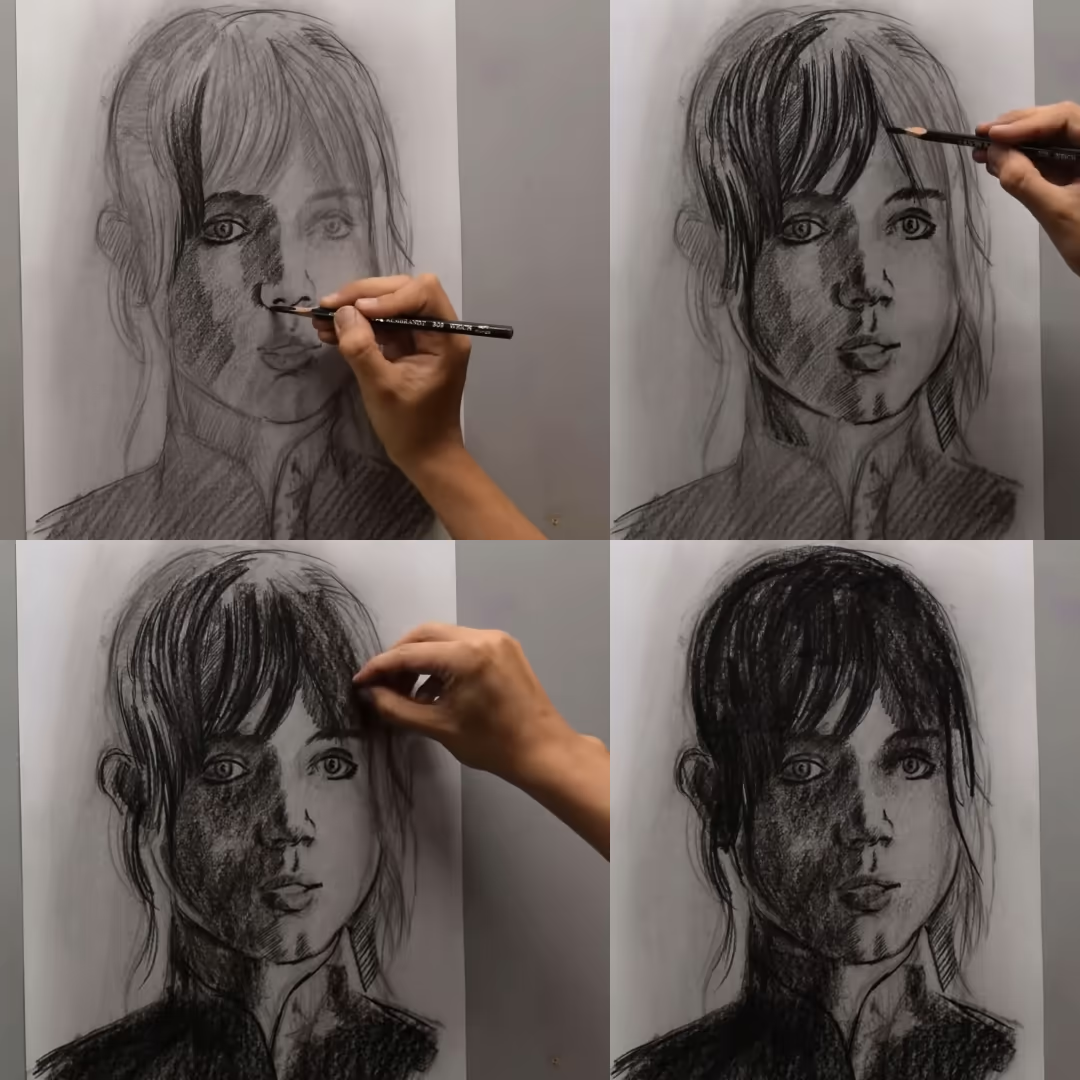

He looked at the drawing one more time, and although he knew it was good, he didn’t sign it. He secretly wanted the teacher to tell him to do so.

While waiting for the teacher, he looked at the other candidates. They were amazed by their results as well, and they were leaving the classroom looking at their pieces with great pride. The pride he could only bet on this teacher’s approval.

Finally, the teacher came by his easel, took a quick look, and calmly told him: “Tear it up.” Cesar’s disappointment made him lower his head, but he sharply straightened it up as if he had meant to nod. While the teacher left, he thought: Today, besides controlling my hand, I need to control my whole body. Today, I’m an artist but also a soldier.

Without thinking further, he tore up his drawing. When the teacher heard that clean cut, he turned around. “Bring your brushes on Monday. I will teach you painting.”

Cesar woke up on Monday ready for his first day of class. It was far from any other first day. He felt as if he had known the teacher for years.

He arrived early, and to his surprise, the teacher was already there. Moreover, he was welcoming each student with a warm good morning.

Cesar wondered if the teacher had been cold on purpose during the audition, or if he was different in class. Maybe it was a bad day, and today he’s fine, was his last thought.

“Welcome, ladies and gentlemen. Today we are going to continue with last week’s lesson. No, I’m not going to ask you to tear up your paintings.” He paused for a collective sigh. “Today, you’ll paint with water.”

“Watercolor…” said a student.

“Water. You’ll paint anything you want with plain water.”

Cesar took a brush and started painting steady horizontal lines from the bottom edge up to the lower third of that dark canvas. Then, he painted a big sun setting down on the horizon. He paused to think about how he would have mixed its color. Like a musician with perfect pitch, Cesar could call out the exact amounts of paint to make any color. When he finished mixing it in his mind, he noticed that the horizon line started to dry out, and he heard: “Keep painting. Keep painting.” He couldn’t tell if he imagined it or if the teacher said it.

“Notice the difference?” the teacher asked the watercolor student.

“Yes, it vanishes.”

“Notice the difference?” he asked Cesar, who said nothing at first.

The answer must be the lesson, Cesar thought. Subconsciously, his focus shifted from his painting to himself painting. My arm is not rigid, he felt. “I’m painting more relaxed, sir.”

“That’s close, but keep painting.”

Right, tearing up the drawing wasn’t relaxing at all. Why do I trust this man? Of course, his paintings. Trust him, keep painting.

A student snapped with satisfaction: “Sir, results don’t matter.” The teacher quickly replied: “They matter.” His tone added: Don’t forget it.

When the time was up, Cesar looked around and saw that the student next to him was painting a circle over and over. Cesar couldn’t stop imagining him drilling a hole through the canvas.

Patience! That’s it. Patience is the lesson. Wait. I mean tolerance. Patience — water. Tolerance — tearing up the drawing. But that can’t be; he’s an art teacher, not my mom. Walking back home, he kept repeating to himself: erasing; tearing it up; painting with water.

At home, Cesar kept painting and watched every single stroke disappear. His mom asked: “Do you need money? That’s the cheapest paint I’ve ever seen.”

“No, Mom. I’m fine, thank you.”

“Why are you painting with water?”

“That was today’s lesson.”

“And for how long do you have to practice that? The priest is coming by, and I don’t want him thinking you need money for school.”

“I’m not practicing, Mom.”

“Sorry, I forgot for a second how much you love painting.”

He put his brush down and went outside with a big smile. He looked at the sunset, but this time it made him feel something different. Today, that color was more than a mix of red and yellow. It was the exact color his soul was glowing.

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. As the semester is about to end, I want to do something different these last two days. But first, thank you for staying with me. Thank you, Guillermo, Melissa, María, and Cesar. It’s been a great pleasure.”

He went to the classroom next door and brought back the girl they had drawn on the day of the audition. “I’m sure you remember her, and I know you wanted to keep those drawings.” A slight pause was his only apology. “Today, you will paint her, and I want you to keep the painting for the rest of your lives… You may begin.” He wanted to avoid interfering with the lesson in any way, so he headed to his office. There, he hoped for the impossible for three long hours.

He closed his eyes for a few seconds before entering the classroom afterward. He walked straight to his desk, but he didn’t sit down. He said: “As you may know, all of you have a C. It’s an honestly earned one. I hope you are proud of it.”

He wanted to take a glimpse at all the paintings, but he went one by one.

“Guillermo, the scratch on the table, why didn’t you paint it?”

“Sir, I don’t paint those things.”

“Melissa.”

“It’s not beautiful.”

“Maria.”

“I didn’t see it.”

“It’s a fixable defect,” said Cesar.

He walked back to the table. “Maria, come here.” Melissa paid close attention to every movement Maria made. “Can you see it now?” “Sir, I can see it from my chair. I didn’t see it in my painting.”

With a hand gesture, he told her to sit back. While she sat down, he looked straight into her eyes. “Now you have a B.” He walked around the students: “So do you. You. And you. I’ll see you on Friday for the A.”

Maria’s eyes watered on the last ‘you’, and she dropped a tear and said: “That’s just water for painting.”

On Friday, the teacher didn’t come to class. He left a note on each student’s chair with an assignment based on their weakest point. The blackboard said: I’ll be in my office until midnight.

Melissa had to paint a portrait illuminated by a red light. Although her skin colors were perfect, they were always the same ones.

Cesar’s note said: You can paint like a master, but can you paint like a joyful kid? He grabbed the note and went outside thinking of Picasso’s famous line: ‘It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.’ He walked back and forth in the hallway. Then, downstairs accelerating each step.

While he was crossing the road, each step reminded him of something different. I’m going nowhere, he thought and stopped on the other side, next to the cattle field. He was about to climb over the fence, but he lay flat and rolled underneath it. He smiled. That’s how he used to cross them as a child. He didn’t have to run across the field. When he saw the cows at a distance, he said: “Good God!” He remembered the days when his mom couldn’t afford milk. He had wanted nothing more than a cow at home.

I want a cow in my exhibitions; a holy cow! he thought on his way back. He made a few drafts. One showed a cow contemplating dozens of paintings of lovely blue and green grass fields. He knew it was impossible to paint all that in a day, so he drafted a cow looking at a single painting, he liked it. But this is not going to get me an A, he thought. He went outside, and as he didn’t want to focus on any particular idea, he just looked at the horizon. When he brought the cow into his mental picture, he said out loud: “This is it!” He juxtaposed the cow with a painting within the painting. He quickly drafted it: Mission accomplished.

He painted all day. His eyes felt tired. I can’t be sleepy, he thought, not realizing that today he had blinked less than a baby. He closed his eyes, trying to squeeze out some moisture, and then opened them while stepping back.

He took a photo of the painting and walked to a cafeteria that had closed hours ago, and sat on the stairs. When he noticed the horizon of the sub-painting, he said out-loud: “Sorry, my little cow.” He previewed a few color adjustments in an app, and headed back for the final touches.

When he finished the painting, he headed to the teacher’s office. He grabbed the painting not like a masterpiece but like a shield.

The teacher looked at the painting, and while getting closer to it, said: “Cesar… sign it.”

Cesar headed back to the classroom, imagining how his signature would look on the painting, but as he entered, he noticed from a distance that Melissa was staring at her work in frustration. He knew the worst thing he could do was rub in his A by signing the painting. So instead, he put his brushes in mineral spirits and went to her. “Tell me,” he said.

“She needs to be illuminated by a red light.”

Seeing no hint of such light, Cesar said, “Glaze it.”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s easier if I show you.”

“OK.”

He grabbed two heat guns from a drawer.

“No! It’s going to crack the paint,” she said.

He knew the teacher wouldn’t mind cracked paint. “Not if I heat it from the back.”

“Don’t melt it.”

“Take this one; hit it from the front.”

When it had dried, he took her heat gun, touched her shoulder and put back the heat guns. While she sat down, she pressed her fingers against the warm paint. It’s cracking. She looked at Cesar approaching with a glass of sharply smelling solvent. He’s going to throw that on my paint. She watched the glass closely until she saw him dip his brush into it. She felt a squeeze in the middle of her chest when she realized such a modest brush was about to touch her painting.

He bent over the canvas and began preparing the glaze on the side. Suddenly, he covered the portrait with long, bloody up-and-down strokes.

She stared at her painting ruined in red, and felt all the pain she had thought of earlier. She stood up, left the classroom, and without looking back, screamed: “Envy!”

Cesar stood still looking at her leaving the room, her last step turned into a night sky framed by that door. He squeezed his eyes shut longer than ever, and the solvent’s smell had shifted from a clean sensation to pain in his soul. He lowered his head and couldn’t find a trace of the soldier’s spirit he relied on. He sat half-collapsed, hands at the sides of his head. There he was thinking of an unfinished painting. He knew he shouldn’t complete, but also knew he would have ruined if he didn’t. The open working time of the glaze had already begun to tick away.

He went to the teacher’s office. “What if I don’t sign it?”

“That’s a question I can’t answer, Cesar.”

“I’ll get a B.”

“Complete it, Cesar.”

She never saw the result.

Years later, Cesar became a teacher as well. On the first day of class, his students had to draw from an upside‑down reference. He explains:

“We all have preconceptions. We form opinions without adequate knowledge. Drawing is no different. When we draw an ear, we think we already know what it is. We’ve drawn many, but we’ve seen few.

“By drawing upside down you will learn a way to stay true to form. Outside class, you may trace with any technological aid you wish. From camera obscuras to augmented-reality overlays, you name it.

“Is that cheating…? No, it’s not. Painting is not skill-bragging.

“Outside, you’ll also decide if your paintings stay true to form. That’s your choice. But it’s not a choice if you can’t draw.”

The End

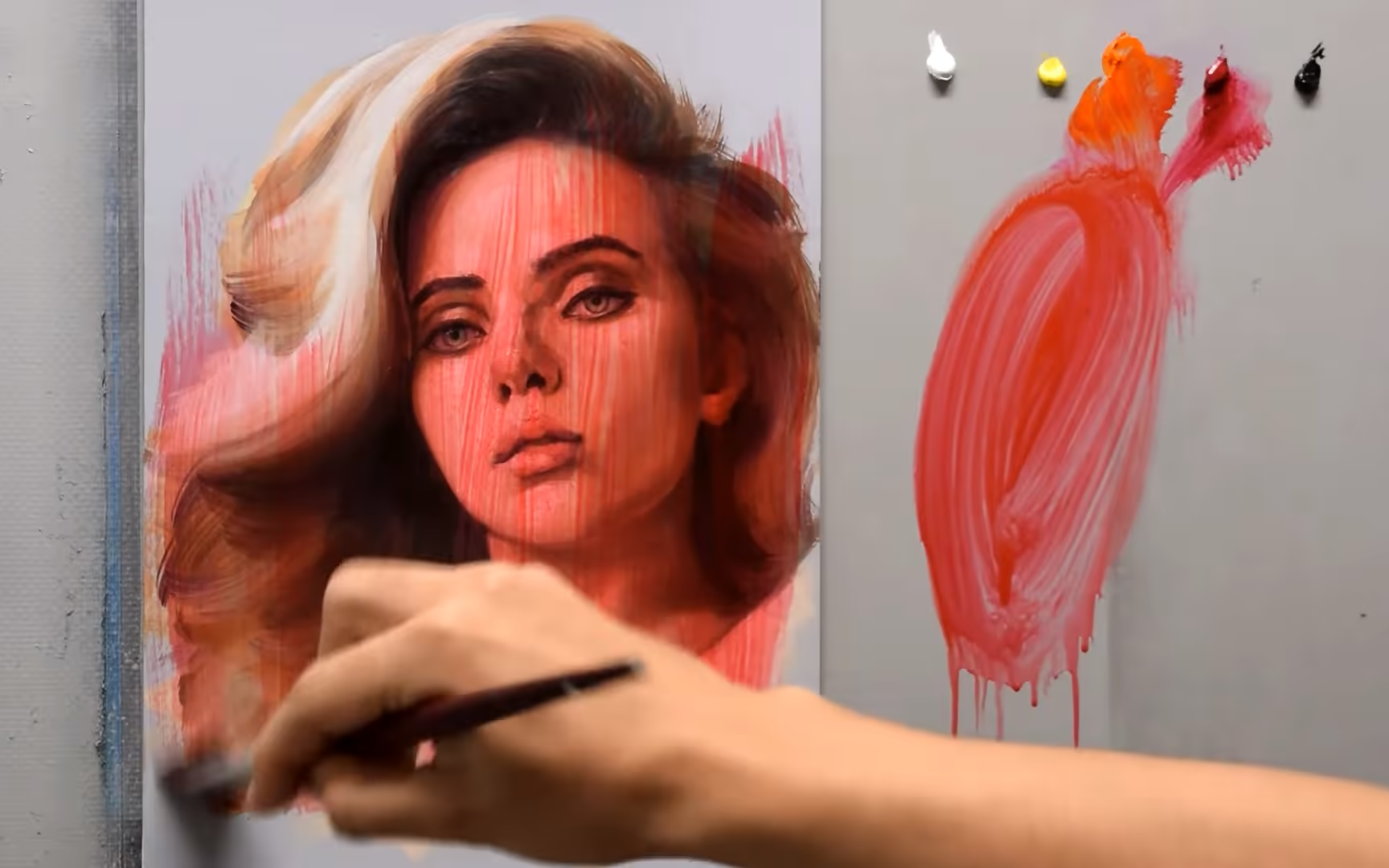

Based on a true story. You can listen to Cesar Cordova telling it while drawing the girl in his YouTube video: The Reason Why You Should Destroy Your Work.